The Photoelectric Effect

What's the photoelectric effect?

What's the photoelectric effect?

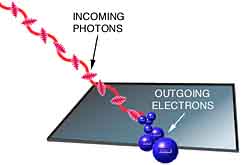

It's been determined experimentally that when light shines on a metal surface, the

surface emits electrons. For example, you can start a current in a circuit just by

shining a light on a metal plate. Why do you think this happens?

It's been determined experimentally that when light shines on a metal surface, the

surface emits electrons. For example, you can start a current in a circuit just by

shining a light on a metal plate. Why do you think this happens?

|

|

Well...we were saying earlier that light is made up of electromagnetic waves, and that

the waves carry energy. So if a wave of light hit an electron in one of the atoms in

the metal, it might transfer enough energy to knock the electron out of its atom.

Well...we were saying earlier that light is made up of electromagnetic waves, and that

the waves carry energy. So if a wave of light hit an electron in one of the atoms in

the metal, it might transfer enough energy to knock the electron out of its atom.

Okay. Now, if light is indeed composed of waves, as you suggest...

Okay. Now, if light is indeed composed of waves, as you suggest...

|

What do you mean, "if light is composed of waves"? Is there another option?

What do you mean, "if light is composed of waves"? Is there another option?

|

Historically, light has sometimes been viewed as a particle rather than a wave;

Newton, for example, thought of light this way. The particle view was pretty much

discredited with Young's double slit

experiment, which made things look as though light had to be a wave. But in the

early 20th century, some physicists--Einstein, for one--began to examine the particle

view of light again. Einstein noted that careful experiments involving the

photoelectric effect could show whether light consists of particles or waves.

Historically, light has sometimes been viewed as a particle rather than a wave;

Newton, for example, thought of light this way. The particle view was pretty much

discredited with Young's double slit

experiment, which made things look as though light had to be a wave. But in the

early 20th century, some physicists--Einstein, for one--began to examine the particle

view of light again. Einstein noted that careful experiments involving the

photoelectric effect could show whether light consists of particles or waves.

How? It seems to me that the photoelectric effect would still occur no matter which

view is correct. Either way, the light would carry energy, so it would be able to

knock electrons around.

How? It seems to me that the photoelectric effect would still occur no matter which

view is correct. Either way, the light would carry energy, so it would be able to

knock electrons around.

Yes, you're right--but the details of the photoelectric effect come out

differently depending on whether light consists of particles or waves. If it's waves,

the energy contained in one of those waves should depend only on its amplitude--that

is, on the intensity of the light. Other factors, like the frequency, should make no

difference. So, for example, red light and ultraviolet light of the same intensity

should knock out the same number of electrons, and the maximum kinetic energy of both

sets of electrons should also be the same. Decrease the intensity, and you should get

fewer electrons, flying out more slowly; if the light is too faint, you shouldn't get

any electrons at all, no matter what frequency you're using.

Yes, you're right--but the details of the photoelectric effect come out

differently depending on whether light consists of particles or waves. If it's waves,

the energy contained in one of those waves should depend only on its amplitude--that

is, on the intensity of the light. Other factors, like the frequency, should make no

difference. So, for example, red light and ultraviolet light of the same intensity

should knock out the same number of electrons, and the maximum kinetic energy of both

sets of electrons should also be the same. Decrease the intensity, and you should get

fewer electrons, flying out more slowly; if the light is too faint, you shouldn't get

any electrons at all, no matter what frequency you're using.

That sounds reasonable enough to me. How would the effect change if you assume that

light is made of particles?

That sounds reasonable enough to me. How would the effect change if you assume that

light is made of particles?

I should give you some background information on this, first. It all began with some work

on radiation by Max Planck...

I should give you some background information on this, first. It all began with some work

on radiation by Max Planck...