Evidence for a Nucleus

One of Thomson's most radical (and, as it turned out, best) ideas was to

suggest that the electrons he'd discovered were part of the chemists' atoms.

This contradicted Dalton's idea that atoms were "uncuttable," with no

smaller parts. It did seem to make sense, though: Thomson knew that

electric currents can be started by chemical reactions (as in a battery) and

by light shining on metal, in the photoelectric effect, so

electrons must have some connection with the world of atoms.

One of Thomson's most radical (and, as it turned out, best) ideas was to

suggest that the electrons he'd discovered were part of the chemists' atoms.

This contradicted Dalton's idea that atoms were "uncuttable," with no

smaller parts. It did seem to make sense, though: Thomson knew that

electric currents can be started by chemical reactions (as in a battery) and

by light shining on metal, in the photoelectric effect, so

electrons must have some connection with the world of atoms.

But if atoms have electrons in them, why are they electrically neutral?

They have to have a positively charged part, to cancel out the negative

electrons.

They have to have a positively charged part, to cancel out the negative

electrons.

Exactly. Thomson's original picture of the atom was

called the "plum pudding model," though, in the spirit of the modern

age, I prefer to think of it as the "chocolate

chip cookie model." The electrons were the "chips," embedded in a

positively charged hunk of "cookie dough." Exactly. Thomson's original picture of the atom was

called the "plum pudding model," though, in the spirit of the modern

age, I prefer to think of it as the "chocolate

chip cookie model." The electrons were the "chips," embedded in a

positively charged hunk of "cookie dough."

|

|

| In 1911, Ernest Rutherford announced experimental evidence showing that the cookie model was wrong. |

|

| Rutherford's experiments consisted of shooting alpha particles at thin sheets of metal. He then measured the angles at which they came sailing out. |

So what happened?

So what happened?

Based on Thomson's model, Rutherford assumed the flying, positively charged

alpha particles would be pushed a little to the side by the positive "cookie

dough" in the metal atoms, and continue flying along at a slightly different

angle. He was shocked by what he actually saw. Most of the alpha particles

went right through the metal without changing course at all, but a few turned

a full 180 degrees and went shooting back the way they'd come.

Based on Thomson's model, Rutherford assumed the flying, positively charged

alpha particles would be pushed a little to the side by the positive "cookie

dough" in the metal atoms, and continue flying along at a slightly different

angle. He was shocked by what he actually saw. Most of the alpha particles

went right through the metal without changing course at all, but a few turned

a full 180 degrees and went shooting back the way they'd come.

|

|

Rutherford compared the experience to shooting an artillery shell at a

piece of tissue paper--and seeing the shell bounce back.

And that meant the cookie picture was wrong?

And that meant the cookie picture was wrong?

If the positive charge were spread throughout the whole atom, as

in the cookie model, Rutherford calculated that there would be no

possibility of the particles bouncing back that way. The only way his

results made sense was if he assumed that all the positive charge, and

almost all the atom's mass, was concentrated in a tiny lump at the

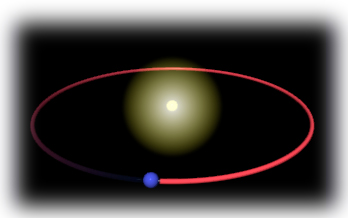

center--what we now call the nucleus. He imagined the electrons orbiting

around the nucleus like planets around the sun, with a (relatively) huge

empty space between them.

If the positive charge were spread throughout the whole atom, as

in the cookie model, Rutherford calculated that there would be no

possibility of the particles bouncing back that way. The only way his

results made sense was if he assumed that all the positive charge, and

almost all the atom's mass, was concentrated in a tiny lump at the

center--what we now call the nucleus. He imagined the electrons orbiting

around the nucleus like planets around the sun, with a (relatively) huge

empty space between them.

Rutherford's model had a few problems, which helped inspire the development

of quantum mechanics--I've told that story more fully elsewhere. The current picture of

the atom has the electrons not orbiting but in "clouds" at different energy

levels--see the Schrödinger

Model or the Elements as Atoms

section for more details.